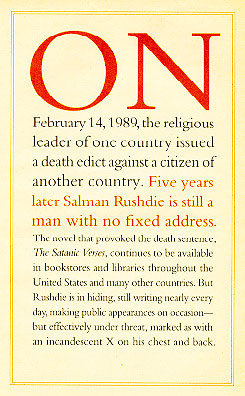

In 1994 Don DeLillo and Paul Auster authored the pamphlet shown below, in a effort to raise awareness about the plight of Salman Rushdie.

The full text is below:

On February 14, 1989, the religious leader of one country issued a death edict against a citizen of another country. Five years later Salman Rushdie is still a man with no fixed address. The novel that provoked the death sentence, The Satanic Verses, continues to be available in bookstores and libraries throughout the United States and many other countries. But Rushdie is in hiding, still writing nearly every day, making public appearances on occasion -- but effectively under threat, marked as with an incandescent X on his chest and back. His novel is a cultural epic and so is the controversy. It involves the anger of Britain's immigrants from Pakistan, India, and other countries. It bears strongly on the American tradition of free expression. It includes riots and book-burnings. It has involved mullahs, presidents, demonstrators, diplomats -- and a murdered Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi. And it is linked to the continuing impact of world Islam on the consciousness of the West.

Now the world has grown smaller around this man. He is distanced from the people who have nourished his work and severed from the very texture of spontaneous life, the tumult of voices and noises, the random scenes that represent the one luxury writers thought they could take for granted.

Not any more.

He is alive, yes, but the principle of free expression, the democratic shout, is far less audible than it was five years ago -- before the death edict tightened the binds between language and religious dogma.

In a real sense Rushdie has become a messenger between readers and writers. He reminds us all how sensitive and precious this collaboration is, how deeply dependent on individual thought and free choice. Every book carries the burden of giving offense. But there is an intimate contract between the two participants, a joint effort of mind and heart that allows for thoughtful differences and that thrives on the prospect of understanding and conciliation.

This is where the spirit of Rushdie lives, in the narrow passage between the writer who works in solitude and the reader whose own living space or park bench or plane seat is "the little room of literature" -- in Rushdie's own phrase -- the place that will not be completely open until all marked writers are free people again.

What can we do? We can think about him. Try to imagine his life. Write it in our minds as if it were the most unlikely fiction.

And we can hope that our government and others will exert due pressure to return Salman Rushdie -- and all other threatened writers -- to the world. His world and ours. More than ever it is one place, and a shadow stretches where a man used to stand.