This page lists the various non-fictional pieces of writing by DeLillo (most recent on top).

A short piece entitled 'Remembrance' appears in Granta 108: Chicago, on Nelson Algren. Note that DeLillo met Algren in the early sixties when Algren lived on Long Island, and there was correspondence between the two through the decade.

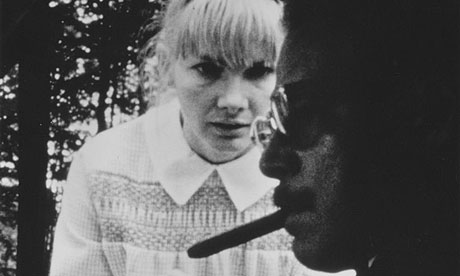

This piece appears in Black Clock #4 (late 2005), pages 56-59, with eleven numbered sections. The subject is the film "Wanda" from 1971, the only film directed by Barbara Loden. Loden plays Wanda, a woman adrift, who finds herself hooked up with a bank robber played by Michael Higgins.

DeLillo uses the piece to continue his comments on film. A couple bits:

When I get together with writers I know, we don't talk about books. We talk about movies. This is not because we see the mechanism of the novel operating in certain films, ranging from Kieslowski to Malick. It's because film is our second self, a major narrative force in the culture, an aspect of consciousness connected at some level to sleep and dreams, as the novel is the long hard slog of waking life.

When reality elevates itself to spectacular levels, people tend to say, "It was like a movie." Wanda takes the movie sensation and denatures it, turns it into dullish daily life, with the jerky gait of a woman walking a dog.

The piece is now available online at the Guardian: Woman in the distance published November 1, 2008. It appears to be the full piece, but the numbering is removed. The piece has also been published in 2008 in the initial edition of a new periodical called Artesian out of England.

This piece appears in the Spring 2004 issue of Grand Street, issue 73 entitled Delusions. There are 11 pages of writing, accompanied by film stills and photos, running on pages 36-53. The movies are The Fast Runner (the film of Inuit legend), Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould and Straight, No Chaser (on Thelonious Monk). The book is The Loser by Thomas Bernhard, which images Bernhard the narrator as a friend of Glenn Gould. The old photograph is one of Monk, Charles Mingus, Roy Haynes and Charlie Parker. This musing touches on issues of long standing in DeLillo's work: the life of the artist, the solitary nature of art-making, the art-making obsession that can go over the edge, the relationship of the artist to the audience.

DeLillo writes of Bernhard: "It has to be understood that Bernhard himself wites a prose so unrelenting in its intensity toward a fixed idea that it sometimes approaches a level of self-destructive delirium. He is frequently funny at this level."

And of Monk: "Monk wrote a tune called Introspection. Two minutes twelve seconds (or more, or less, depending on which recording you listen to). But what happens when introspection develops a density that obliterates the world around it?"

To mark the passing of 40 years since the assassination, Frontline has posted a question and answer forum entitled Oswald: Myth, Mystery and Meaning with responses from DeLillo, Edward J. Epstein and Gerald Posner (DeLillo's comments only were later published as "The American Absurd" in Harper's, Feb 2004). Here are a couple excerpts from DeLillo responses:

What happened during that moment in Dallas, and in the months and years before -- in Oswald's life -- that we can determine with certainty? How did such a vivid fragment of reality, caught on film before hundreds of witnesses, with trained security personnel on the scene, become so deeply lost in the maze of documentation, dispute, rumor, paradox, lies, dreams, illusions, ideologies, absurdities, murders, suicides and endlessly suggestive human involvements?

Something happened. Oswald fired three shots from the sixth-floor window. But was there something else -- a clear motive, a larger design, a second gunman? The truth is knowable. But probably not, ever, incontrovertible.

Oswald changed history not only through his involvement in the death of the president, but also in prefiguring such moments of the American absurd. He was not media-poisoned, as many of the others have been, and his crime was not steeped in the supermarket cult of modern folklore and dread. But think of the outrages and atrocities that flowed from the psychic disorientation of the 1960s -- the assassinations, the cult murders, the mass suicides. It was surely the assassination of President Kennedy that began to give us a sense of something coming undone. This was vintage American violence, lonely and rootless, but it shaded into something older and previously distant, a condition of estrangement and helplessness, an undependable reality. We felt the shock of unmeaning.

Conjunctions (Fall 2003, issue 41), contains a short piece from DeLillo on William Gaddis. Read it all here.

Years later, when I was a writer myself, I read JR, and it seemed to me, at first, that Gaddis was working against his own gifts for narration and physical description, leaving the great world behind to enter the pigeon-coop clutter of minds intent on deal-making and soul-swindling. This was not self-denial, I began to understand, but a writer of uncommon courage and insight discovering a method that would allow him to realize his sense of what the great world had become.

A one page reflection on the title drawing, to which DeLillo gives a bit of a recursive turn. This piece appears in the Paris Review, Fall 2003 issue (#167), and is part of a section called 'Reading and Readers' of writers' impressions on art works from a collection that features people reading.

A piece on a memory of a brief sighting of a movie star, with musings on the nature of our shared memories of movie moments, and the strange nature of connections in our minds. This appeared in The New Yorker, October 20, 2003, pp. 76-8.

Every memory we have is, finally, of ourselves. If the memory of an experience is flawed, there is a rift in the continuity of self. I see the man to her left, or imagine him, maybe, reformulate him--cropped hair and a six-day beard that comes close to matching the residue on his head. There is less of us with each depleted memory.

...

There are other hotbeds of memory, such as baseball, of course, rich in the mellow lore of names, dates and arcane stats. But in film it is the image, most strikingly, that clings, sometimes to a face or a gesture, sometimes an isolated scene. ... We have no way of knowing with whom we share the memory of such scattered images. Imagine an immense global brain sprouting organically in the Arizona desert -- but that's a movie in itself, from the science-fiction fifties.

I note the connection to DeLillo's personal concerns about memory, as described in Ralph Gardner's 1997 NYT piece "Writing That Can Strengthen the Fraying Threads of Memory" (check Bibliography for details).

This short essay appeared in Harper's magazine, December 2001 issue, pages 33-40. It concerns the Sept 11 incidents, terrorism, and America. It consists of eight numbered sections. Here are a few excerpts:

Technology is our fate, our truth. It is what we mean when we call ourselves the only superpower on the planet. The materials and methods we devise make it possible for us to claim the future. We don't have to depend on God or the prophets or other astonishments. We are the astonishment. The miracle is what we ourselves produce, the systems and networks that change the way we live and think.

....

Now a small group of men have literally altered our skyline. We have fallen back in time and space. It is their technology that makes our moments, the small lethal devices, the remote-control detonators they fashion out of radios, or the larger technology they borrow from us, passenger jets that become manned missiles.

Maybe this is a grim subtext of their enterprise. They see something innately destructive in the nature of technology. It brings death to their culture and beliefs. Use it as what it is, a thing that kills.

This piece is the acceptance address given by DeLillo on the occasion of being awarded the Jerusalem Prize in 1999. A small pamphlet was printed with this address, an address by Scribner editor-in-chief Nan Graham, the Jury's Citation and an address by Jerusalem mayor Ehud Olmert. It was reprinted in a German translation in Die Zeit in 2001.

The piece is in five numbered sections, and is about five pages long. Here is one short passage, listing the possible novels that the writer might be working on...

The novel of ideas. The novel of manners. The novel of grim witness. The novel of pure dreaming. The novel of excess. The novel of unreadability. The comic novel. The romance novel. The epistolary novel. The promising first novel. The sad, patchwork, grave-robbing, over-my-dead-body posthumous novel. The suspense novel. The crime novel. The experimental novel. The historical novel. The novel of meticulous observations. The novel of marital revenge. The beach novel. The war novel. The antiwar novel. The postwar novel. The out-of-print novel. The novel that sells to the movies before it is written. The novel that critics like to say they want to throw across the room. The science fiction novel. The metafiction novel. The death of the novel. The novel that changes your life because you are young and open-hearted and eager to take an existential leap.

DeLillo also quotes from Gaddis.

In the Sept. 7, 1997 issue of the New York Times Magazine, an essay entitled "The Power of History" appears. DeLillo discusses his use of fact in his fiction.

A short piece ran in The New Yorker on May 26, 1997, pages 6-7. An address delivered on May 13, 1997 at the New York Public Library's event "Stand In for Wei Jingsheng."

Here's more about the event.

The piece consists of eleven numbered paragraphs, intertwining the story of a Russian performance artist impersonating a dog in a cage, Kafka's Hunger Artist, and Wei Jingsheng.

The final paragraph:

The deeper they conceal him--the more remote the cell, the smaller the cell, the colder and stonier the walls of the cell--the move vivid and living is the writer.

In 1996 Quill & Brush published a limited (500) edition chapbook on the occasion of the 100th birthday of F. Scott Fitzgerald, entitled 'F. Scott Fitzgerald at 100 - Centenary Tributes by American Writers.' DeLillo contributed a short piece entitled 'Fitzgerald : the Movie' and here it is:

The document at hand is the Bantam edition of The Great Gatsby, 1974, timed to coincide with the release of the major motion picture. We find the two stars photographed on the cover and a section of movie stills inserted within, sixteen pages of overproduced suits, dresses, hair styles and automobiles--an unintentional echo of Gatsby's imitation villa.

There is also a novel in these pages. And all the reader has to do is find the text and isolate it from the images, from the enormous hovering presence of the misbegotten movie.

We want to believe there will always be such readers, men and women able to pry a sense of a great writer's work from the acts of terror that bombard it. We want a 1925 novel to be innocent of postmodern iconic complications. Fitzgerald/Gatsby/Redford. Who is the figure of stricken glamour here? In the end Fitzgerald's importance will rest on our ability to see him clean.

This, interestingly, may become easier as time passes and old romantic projections begin to fade. Fitzgerald the cultural figure, a misty sort of man-legend, may yield ever more surely to Fitzgerald the artist--the writer of clear bittersweet knowing prose and the creator of large and sad American lives.

In 1994 Don DeLillo and Paul Auster wrote a piece in defense of Salman Rushdie, and you can find it here.

Here's a group letter signed by DeLillo that ran in the New York Times:

"Rushdie Novel Stirs Passions East and West; Answer to the Cardinal"

Date: February 26, 1989, Sunday, Late City Final Edition Section 4; Page 22, Column 5; Editorial Desk

To the Editor:

John Cardinal O'Connor has not read, does not intend to read, but criticized Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses, while he proclaimed his "sympathy for the aggrieved position the Muslim community has taken on this problem" and "deplored any and all acts of terrorism that would be engaged in" in connection with the book (news story, Feb. 20).

The undersigned writers, of widely varying Roman Catholic backgrounds, deplore the moral insensitivity to the plight of Mr. Rushdie and an ecumenical zeal that would appear to support repression. We cannot see how the Cardinal's call on Catholics to work with Muslims to achieve mutual understanding and promote peace, freedom and social justice can be implemented by a position that censors the basic freedoms to write, to publish and to read that give life and possibility to such understanding.

A spokesman for the Cardinal reports that Cardinal O'Connor said of the novel that "he trusted the judgment of Catholics as being mature and recognizing the affront it poses to believers in Islam."

Mature Catholics do not believe that any dialogue with the non-Christian world can be conducted within a system that prejudges books. Mature Catholics do not believe that a death threat can be met with ambiguity.

DON DeLILLO, MARY GORDON, ANDREW GREELEY, JOHN GUARE, MAUREEN HOWARD, GARRY WILLS

New York, Feb. 21, 1989

The letter was also signed by 11 other writers.

Published in Dimensions - A Journal of Holocaust Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1989). Reprinted in full in the critical edition of White Noise (1998), and in the Library of America edition Don DeLillo: Three Novels of the 1980s (2022).

This is an interesting essay which I can't easily summarize, but will just give a taste of:

It's all mixed together, routinely braided into our lives--murder, torture, superstition, satire, grueling human ordeal. Information shades into rumor and mass fantasy, which convert to topical entertainment. Our levels of perception begin to blend. It isn't always easy to separate disease from its mythology or violence from its trivialization. Not that we're necessarily eager to make distinctions.

Published in Rolling Stone, Dec. 8, 1983.

Reprinted in the Library of America edition Don DeLillo: Three Novels of the 1980s, 2022.

A precursor to Libra. A short excerpt:

Americans, for their own good reasons, tend to believe in lone gunmen. A stranger walks out of the shadows, a disaffected man, a drifter with three first names and an Oakie look about him, tight-lipped and squinting. We think we know exactly who he is.

What has become unraveled since that afternoon in Dallas is not the plot, of course, not the dense mass of characters and events, but the sense of a coherent reality most of us shared. We seem from that moment to have entered a world of randomness and ambiguity, a world totally modern in the way it shades into the century's 'emptiest' literature, the study of what is uncertain and unresolved in our lives, the literature of estrangement and silence. A European body of work, largely.