Interviewers want to feel that they're cracking a barrier that doesn't exist. I've been called 'reclusive' a hundred times and I'm not even remotely in that category. But people want to believe this because it satisfies some romantic conception of what a dedicated writer is and how he ought to live. 'I know you never do interviews.' They say that to me all the time. 'But here I am' is my stock reply. --DeLillo, in the 1992 Washington Post interview

This page includes interesting bits from various interviews DeLillo has given over the years. For a more complete list of interviews, please consult the Bibliography page. You may also want to take a look at the DeLillo on Radio page for some audio interviews.

As part of a promotion for White Noise, Don DeLillo and Kae Tempest discuss novels, America, and the unwritable (with audio also, which has additional content!). Here's a bit:

Kae Tempest: Is there anything unwritable? Something you want to keep in life and not take to fiction?Don DeLillo: That’s a good question. The first thing to say is I wouldn't consider taking it to fiction unless it prompted me to. There are things, maybe a death in the family or something, that I have no intention of writing about so it doesn’t become a question of choosing to do it against my better judgement.

Following the conference held in Paris in February 2016 (which DeLillo attended), Peter Boxall sent a set of questions regarding the soon-to-be-published Zero K, and received back seven typed pages from the author. Here's a taste:

Twenty-first-century conditions: toward the end of the novel one of the Stenmark twins comments forcefully that there is war everywhere, interspersed with one or another form of terrorism. Is this to be the new century's persistent narrative, counterbalancing the possibility of life extension?It can't be that simple. There is a general dissatisfaction nearly everywhere, it seems, and there is also the simple and sometimes brutal force of nature.

Cyberattacks, cyberwars, the unseen 'terror' of the internet - thrusts and counterthrusts, the concept of the unknown enemy. And the possibility that the game-like nature of the antagonisms will shift to three dimensions.

In this country the daily disasters of TV newscasts. Tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, wildfires. This is routine, the powerful images, the toll of dead and missing. Then the commercial.

Zero K edges into the future, only to return to street-level life. Taxis, trucks and buses.

Xan Brooks speaks with DeLillo on the eve of the UK premiere of Love-Lies-Bleeding, Don DeLillo on Trump's America: I'm not sure the country is recoverable, published 5 Nov 2018. Here's the take (it used to be real estate that he didn't want to talk about...):

"Oh, I think whatever's going on now seems unique," he says. "The question is whether the situation is terminal. I'm very reluctant to talk about Trump, simply because everybody else is. We're deluged with information about Trump on every level – as a man, as a politician. But what's significant to me is that all of his enormous mistakes and misstatements disappear within 24 hours. The national memory lasts 48 hours, at best. And there's always something else coming at us down the pipeline. You can't separate it all out. You get lost in the deluge."

Paul Wilson was able to get a fun interview with DeLillo, presumably during his recent time in the UK. Don DeLillo: What I've Learned, published 17 June 2016. Here DeLillo on his bachelor days in Manhattan, 1979-1982:

When I lived alone back in the Sixties and early Seventies, all I cooked was bacon and eggs. That was finally pointed out to me that it was pretty unhealthy. I'm a terrible cook. I don't like to cook. It's against my religion. I like to eat, but I just can't cook. There you are — maybe that is one of the reasons I've been married for 40 years.It is important to make decisions based on what you feel to be right. The landlord of my $60-a-month apartment offered to eliminate my rent if I were willing to take out the garbage for everybody in the building. It was actually an interesting proposal. But finally I turned him down because I would have to get up at six in the morning and that did not fit in with my writing routine.

Leading up to DeLillo's appearance in Athens on March 16, 2016, Lefteris Kalospyros filed Don DeLillo on this crazy, puzzling world we live in, published on 12 March 2016. Here DeLillo on his time in Greece, 1979-1982:

My stay in Greece turned out to be crucial to my writing. The language, the people, the history, the walls and monuments with their inscribed letters and words – all of this gave me a sense of the deeper involvement I needed to find in shaping a sentence, and of the visual component, the ‘architectural’ element that is present in letters and words. In a sense what I was doing was rediscovering the alphabet.

On the occasion of being announced as the recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Foundation, AP ran a brief article Don DeLillo receiving honorary National Book Award on 2 September 2015. DeLillo provided a response to questions via fax. Here are a couple nice bits with DeLillo quotes:

Asked to name some young writers he feels an affinity for, he joked that at his age "they're all younger.""Lists are a form of cultural hysteria so let's just say that the strong work keeps coming and that the novel as a form continues to provoke innovation on the part of younger writers," he said. "It's true that some of us become better writers by living long enough. But this is also how we become worse writers. The trick is to die in between."

And…

Don DeLillo is pleased to receive an honorary National Book Award medal for lifetime achievement, but a "little intimidated" by the citation for "Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.""The kid from the Bronx is still crouching in a corner of my mind."

DeLillo read and received an award at the Library of Congress National Book Festival in Washington, DC on Sept. 21, 2013. As part of the event he did a live interview with Marie Arana and short audience QA. The session is available via a YouTube video, and is also available on the Library of Congress site, where there is also a text transcript. The interview covers some biographical details, his writing strategy, and more:

Q: How much are your novels actually plotted in advance?A: They're not plotted at all. They proceed essential sentence by sentence and I -- I find that discovering the structure of a novel is very important and at some point it just occurs to me that the novel ought to proceed in this particular manner -- with this structure. Perhaps symmetrical. Perhaps a structure in which the end of the novel repeats, the beginning of the novel. But in many cases -- not all cases -- in many cases a structure reveals itself. That's how -- that's how I have to put it.

It reveals itself. It's not something I consciously work at.

The Chicago Tribune ran 'Living in dangerous times' a short interview with DeLillo conducted by Kevin Nance, on 12 October 2012. Not a whole lot of new information here, though DeLillo does mention that he's in the middle of another novel. Here's an excerpt from the conversation:

In my experience, writing a novel tends to create its own structure, its own demands, its own language, its own ending. So for much of the period in which I'm writing, I'm waiting to understand what's going to happen next, and how and where it's going to happen.In some cases, fairly early in the process, I do know how a book will end. But most of the time, not at all, and in this particular case, many questions are still unanswered, even though I've been working for months.

And…

Yes, I think my work is influenced by the fact that we're living in dangerous times. If I could put it in a sentence, in fact, my work is about just that: living in dangerous times.

New Orleans Review published "A man in a room: an interview with Don DeLillo" by Kevin Rabalais in June 2012 (Vol. 38, No. 1). The Gale Academic Onefile site has posted the wide-ranging interview from an apparently poor quality scan, found here at the Gale site. Here's a short excerpt from the conversation:

I return to a book occasionally because I think I might gain something from re-reading it. Recently, it's a novel by Max Frisch, which I must have read twenty or thirty years ago, called Man in the Holocene. I recently re-read a few more European novels, The Stranger, Peter Handke's The Goalie's Anxiety at the Penalty Kick. What would I read if I had more time? Would I go back to James Joyce? I'm not sure I would. If I did, I would start with the stories and then re-read Ulysses. I had a personal golden age of reading, in my twenties and into my early thirties, and then my writing began to take up so much time. It's not that reading became subservient, it's just that I don't read as eagerly as I used to.

Cinerepublic posted a short interview with DeLillo (in Italian) centered on the Cosmopolis film, dated 22 April 2012. Another site has posted an English translation which you can find here at Cosmopolis Interviews, which also has interviews with Pattinson and Cronenberg. Here's an excerpt from the conversation:

DeLillo: I really liked Mean Streets. I grew up in the Bronx and Scorsese in Lower Manhattan, in Little Italy, but we shared the same language, the same accents and the same behaviours. Needless to say I was familiar with troublemakers like Robert De Niro's character, I even knew some of them very well. But the most significant experience probably dates back further. I was very young when I saw Marty by Delbert Mann, which takes place where I used to live, in the Italian part of the Bronx. The film was shown in Manhattan, so there were eight of us guys, packed in a car to go and watch it. The opening scene takes place in Arthur Avenue. It was our place! Seeing our street, the shops we patronized, there in a movie theatre, that was amazing. It was as if our very existence was acknowledged. We never would have thought that somebody would make a film in those streets.DeLillo: It is because when I write, I need to see what is happening. Even when it is just two guys talking in a room, writing dialogues is not enough. I need to visualize the scene, where they are, how they sit, what they wear, etc. I had never given much thought about it, it came naturally, but recently I became aware of that while working on my upcoming novel, in which the character spends a lot of time watching file footage on a wide screen, images of a disaster. I had no problem describing the process, that is to say to rely on a visualization process. I am not comfortable with abstract writing, stories that look like essays: you have to see, I need to see.

I look forward to the upcoming novel!

Granta posted a short interview with DeLillo conducted by Yuka Igarashi, dated 10 January 2012. The discussion is on the stories. Here's an excerpt from the conversation:

DeLillo: "'The Starveling' is about an incomplete man and his acquiescence to a static life. The man's refuge is the movies and in the minute-by-minute countdown of his days and weeks, there may be an element of horror; to the man himself, however, there is only the day's schedule, and an abiding sense of being safe."

Grantland posted a short email interview with DeLillo conducted by Rafe Bartholomew, dated 3 October 2011 (the 60th anniversary of the 'shot heard round the world' game. The discussion focuses on 'Pafko at the Wall', and here's an excerpt from the conversation:

RB: If you were going to write a novel of similar scope about post-Cold War America and begin it with a scene at a sporting event, what do you think it might be?DD: To portray America over the past twenty years or so, I would think immediately of football, probably the Super Bowl in its sumptuous suggestion of a national death wish.

The September 2011 issue of The Believer features a conversation between DeLillo and Bret Easton Ellis, hosted by French journalist Didier Jacob in Paris in October 2010. The conversation ranges over both authors' careers. A sidebar features "Lines Spoken by Historical Figures in DeLillo's Underworld" and I liked Jackie Gleason's "Don't be a clamhead all your life." Here's an excerpt from the conversation:

DeLillo: "We don't really know how technology will affect narrative. That's the question. See, people used to say that the novel is going to die, but they would never say that movies will die with it, when in fact all forms depend on the narrative. I think if one of them fails, the others are going to fail as well. Maybe this will happen to both forms, and maybe movies will take a totally different direction with fiction."

St. Louis Beacon: Sept. 17, 2010, an interview with Don DeLillo on the occasion of receiving the Saint Louis Literary Award, "Take Five: Don't call Don DeLillo's fiction 'postmodern'" conducted by Dale Singer.

Q: Do you write shorter novels because the public seems to have a shorter attention span, or because people now read on electronic devices?DeLillo: I would never write in response to what I believe the public wanted or needed.

I do think that in the near future, if it hasn't happened already, people will be able to use technology to design their own novels, perhaps with individuals themselves as the main character. In other words, everything is being individualized and narrowed. Where does that leave the world itself? The world is shrinking into a kind of technological funnel. I think people are drawn into their technological devices, and this becomes a kind of subjective universe, into which much of the rest of the world simply does not enter. I'm not sure what it's leading to ultimately, but it certainly would seem to indicate that people's capacity to learn and get a sense of a wide world seems to be narrowing somewhat drastically.

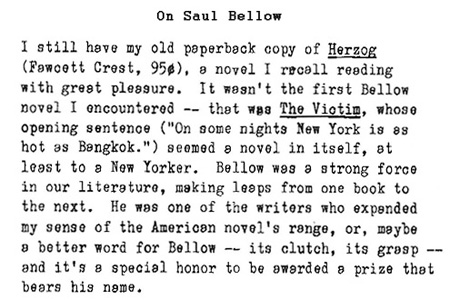

PEN: Sept., 2010, an interview with Don DeLillo on the occasion of winning the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction, "An Interview with Don DeLillo" conducted via fax by Antonio Aiello. Here's part of DeLillo's typed response, and an excerpt:

PEN: In an interview this past March, you noted that your shift, over the last decade, toward shorter novels had been informed by re-reading several slim but seminal European works of fiction, including Albert Camus's The Stranger, Peter Handke's The Goalie's Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, and Max Frisch's Man in the Holocene. Can you talk a little about the evolution of your work and influences?DeLillo: A novel determines its own size and shape and I've never tried to stretch an idea beyond the frame and structure it seemed to require. (Underworld wanted to be big and I didn't attempt to stand in the way.) The theme that seems to have evolved in my work during the past decade concerns time - time and loss. This was not a plan; the novels have simply tended to edge in that direction. Some years ago I had the briefest of exchanges with a professor of philosophy. I raised the subject of time. He said simply, "Time is too difficult." Yes, time is a mystery and perhaps best examined (or experienced by my characters) in a concise and somewhat enigmatic manner. Next book may be a monster. (Or just a collection of short stories.)

Guardian: Aug. 8, 2010, an interview with Don DeLillo on Point Omega and more, "Don DeLillo: I'm not trying to manipulate reality - this is what I see and hear" by Robert McCrum.

So how, I wonder, getting down to it, does he usually go about collecting the materials for his fiction? "I'm always keeping random notes on scraps of paper," he replies. "I always carry a pencil and a notebook. Coming on the train today I had an idea for a story I'm writing and jotted it down - on just a little scrap of paper. Then I clip these together. I'll look at them in, say, three weeks' time, and see what I've got. You know," he adds defiantly, "I've never made an outline for any novel that I've written. Never."

London Times: Feb. 21, 2010, an interview with Don DeLillo on Point Omega and more, "Don DeLillo: A writer like no other" by Ed Caesar.

Point Omega and Underworld do not read like the work of the same author. One is a carnival, the other a chess game. DeLillo, interestingly, feels the same way. He has recently reread Underworld, to answer questions from foreign-language translators. It was, he says, a sobering experience. "In truth, it made me wonder whether I would be capable of that kind of writing now - the range and scope of it. There are certain parts of the book where the exuberance, the extravagance, I don't know, the overindulgence... There are city scenes in New York that seem to transcend reality in a certain way."There is no bitterness in his voice. "In the 1970s, when I started writing novels," he explains, "I was a figure in the margins, and that's where I belonged. If I'm headed back that way, that's fine with me, because that's always where I felt I belonged. Things changed for me in the 1980s and 1990s, but I've always preferred to be somewhere in the corner of a room, observing."

An interview with DeLillo appeared online dated February 1, 2010 in the Barnes and Noble Review, titled Don DeLillo: A Conversation with Thomas DePietro. They discuss Point Omega, among other things. Here's an excerpt:

BNR: To interest Elster in his film idea, Finley follows him to his home in the Southwestern desert, a landscape that's interested you before. Is it the alteration of time and space in the vast emptiness that attracts you?

DD: It was only after I finished work on the prologue that I began to think seriously about what would follow. It occurred to me that two men -- unnamed -- who'd spent a few moments in the screening room would in fact be the main characters in the work ahead. The older man, Elster, and the young filmmaker, Jim Finley. And I knew that the central narrative would take place in an environment very different from that of the dark screening room at the museum. I remembered the desert area, Anza-Borrego, that I'd visited years earlier -- heat, space, sky, enormous distances. Also time -- but not the scrupulously refined time of the 24-hour videowork. This is the vast meditative time of the desert, geologic time, making Elster think about evolution and extinction.

An interview with DeLillo appeared online dated January 29, 2010 in the Wall Street Journal, titled Don DeLillo Deconstructed by Alexandra Alter. They discuss Point Omega, among many other things. Here's one excerpt of interest:

WSJ: Your work has often been described in reviews as being eerily prescient of major social forces of upheaval such as terrorism and the influential power of mass media and technology.

Mr. DeLillo: I don't think it's prescience. Writers, some of us, may tend to see things before other people do, things that are right there but aren't noticed in the way that a writer might notice -- that's all. Certainly I've never tried to imagine what the future will hold. It's a hopeless endeavor to try to do such a thing... There are certain things that people don't pay a deep attention to as they happen. There was terrorist activity in this city in the 1970s, and of course it was noticed, but then it passed, and I noted it and put it in some of my novels. And I suppose the World Trade Center appears in three or four of my novels, which of course does not mean that I expected it to be destroyed. It just means that I saw it.

An interview with DeLillo appeared in the October 11, 2007 issue of Die Zeit (in German), titled 'Ich kenne Amerika nicht mehr' ('I don't know America anymore') by Christoph Amend und Georg Diez. They discuss Falling Man, among many other things. Daniel provides this brief translation excerpt of interest:

ZEIT. What is your political orientation?

DD. I am independent. And I would rather not say anything more about it.

ZEIT. Why not?

DD. Well, in the Bronx where I grew up we'd have put it his way: Because it's none of your fucking business.

ZEIT. For readers of this conversation, we must here add that you are laughing.

And here's a bit from the translation below, referencing Norman Mailer:

Dum Pendebat provides a full translation into English.DD: Naturally a direct comparison of terrorist and novelist is complete nonsense, we both agree on that, right? But there was once a time when the novelist also had some influence on how his contemporaries thought, the way they saw the world, the way they lived. Kafka, Beckett: they succeeded at that. Kafka's work changed forever the way we look at the world. Does literature still have this power? No, I think it has lost this power. Great novels continue to be written, but they are no longer changing the world.

ZEIT: Why not? What makes you so pessimistic?

DD: We live in an age of rapid mass media, television, Internet. They determine our tempo, not books.

ZEIT: But as a novelist who deals with the great themes of our age, aren't you struggling against that?

DD: I have ideas, and implement them. It would scare me if my own books had that kind of influence. I never wanted to change the world. Norman Mailer wanted to, he set himself the task of changing the consciousness of our age. And I think he came pretty close, in the 1960s, to actually managing to do it. But me? No, no, I never wanted anything like that. I'm not Maileresque.

An interesting interview with DeLillo appeared in the July 2007 edition of Guernica magazine, titled 'Intensity of a Plot' by Mark Binelli. They discuss Falling Man, DeLillo mentions Norman Mailer, discusses the sixties and music a bit.

Guernica: What kind of affinity did you feel, if any, towards the Sixties counterculture?

Don DeLillo: Well, I was never either pro-culture or counter-culture. I was in a kind of middle state. It's a little hard to describe, actually. I lived in a very minimal kind of way. My telephone would be $4.30 every month. I was paying a rent of sixty dollars a month. And I was becoming a writer. So in one sense, I was ignoring the movements of the time. My first novel is not deeply involved with any of that.

Guernica: Was this sort of minimalist living part of just being focused, or was it more a factor of you being a poor, struggling writer?

Don DeLillo: More the second than the first. But the fact that a character in my second novel ends up in the West Texas wilderness and a character in my third novel becomes a recluse in a room somewhere is a further indication of my state of mind at the time.

A short interview with DeLillo appeared in the program for 'Love-Lies-Bleeding' at the Steppenwolf Theatre for the premier back in May 2006. This interview is online here, and the questions revolve around his plays.

"In fiction, I tend to write fairly realistic dialogue-not always, and it tends to vary

from book to book. But in many books, there is a colloquialism of address. The characters will speak in a quite idiosyncratic way sometimes. In theater, I tend to write a slightly more formal dialogue. I'm not sure why. It's almost as if I'm writing narration in the form of dialogue. In certain plays that I've done, I think this is true. I don't know the reason. I could conjecture that there's so much colloquial dialogue in American theater that I move in a somewhat different direction. But in this play there's a slight formality to it. Characters don't speak off-the-cuff or don't seem to be. It's not quite that spontaneous."

A short but sharp DeLillo interview with Kevin Gray appears in Details magazine, April 2006, entitled Q&A With Don DeLillo: The novelist on baseball, technology, and how French philosophy has infected the White House..

Q: You've written about how governments can twist reality through language. I was reminded of that recently when a White House official told a reporter, "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality." How does that strike you?A: It's what a French philosopher might have said 20 years ago. The White House has just caught up, but now it's in the real world. It's marched out of philosophy books and into the center of power. And every evidence is that the administration is trying to create a global reality but the reality won't cooperate.

DeLillo spoke with Sid Smith on the occasion of the premier of 'Love-Lies-Bleeding' in Chicago. The interview ran as "Unraveling DeLillo" in the Chicago Tribune, April 30, 2006 (was at http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2006-04-30/news/0604290278_1_novels-ideas-don-delillo but apparently gone from the web). A couple excerpts:

"I'm not sure what compels me one day to sit down and start writing this or that line and simply follow it," he said in a recent telephone interview about "Love-Lies-Bleeding, It's simply a question of following an idea where it leads. I'm not sure I can be anymore enlightening than that. My ideas for any piece have such mysterious origins. A writer decides to follow some ideas and not others for reasons that aren't always clear to him. It's often a matter of intuition."

On the play's title (& the flower): "I think it was first named in the 16th or 17th Century as love lyeth bleeding. I wouldn't make too much of the name or overinterpret the verb. Though others may be tempted to do so. It's hard to know how much an audience absorbs from hearing language spoken versus read on a page. I think in many cases speeches can be elusive, particularly if they're dense with meaning. I don't know if that happens here. It's relatively straightforward dialogue, even if not particularly colloquial. It's somewhat stylized, with elements of rhythm and repetition."

DeLillo speaks with Dominic Maxwell on the occasion of the premier of 'Valparaiso' in London. The interview ran in The Times on April 24, 2006, titled "The accidental playwright".

Q: Does he accept that he'll reach fewer people than he would with fiction?

A: "Oh yes. And it simply doesn't matter. If an idea seems to find its way towards a stage setting, that's the direction I take. I don't know if I'm trying to achieve anything other than to follow an idea on to the page or, in this case, into three dimensions, with an actor and an audience. The idea dictates the medium."

DeLillo speaks with John Freeman in an interview published in the San Francisco Chronicle on March 5, 2006, about Love-Lies-Bleeding, 'Game 6', movies and sports. Column is on the Wayback Machine, and is titled "Q&A: Don DeLillo - It's not as easy as it looks". Run as a verbatim Q&A.

Q: Are you a film buff?

A: I am pretty interested in movies. I don't really have a huge collection, but I'm pretty interested. I did go to see "Satantango." Did you hear about this film? It's a 7 1/2-hour Hungarian film which showed at the Museum of Modern Art last week. Well, I actually saw it this past Monday after missing it on a number of occasions. The house was packed, and through the entire 7 1/2 hours, through two brief intermissions, only one cell phone went off. And I expected the cinephiles in the house to drag the guy out and beat him to death.

Interview/article in Melbourne's The Age, "Lurking around society's edges" on DeLillo and Love-Lies-Bleeding, dated Feb 22, 2006. No byline, but it has some of the same lines as the interview listed above by John Freeman.

"What do you really see? What do you really hear?" DeLillo ponders, when I ask how he stays tuned in to the dream waves of American life. "That's what in theory differentiates a writer from everyone else. You see and hear more clearly," he says.

DeLillo spoke publicly with Greil Marcus at the Telluride Film Festival in September, 2005, and the conversation is published in The Believer, June 2006 issue. The subject of the conversation was Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick after a screening of Scorcese's No Direction Home. The full unedited conversation is available on the Greil Marcus site, and is also on the Believer site.

"See, the genius of rock music is that it matched the cultural hysteria around it. Not only Dylan, but that kind of scorching electric howl of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison-and these happen to be three people who died early and tragically-as if to provide an answer, as if to present a counterpart to what was happening around them in the streets, in the riots, in the assassinations, in the war in Vietnam, in the civil rights struggle. Rock was the art form that could match that."

The first issue of the French magazine Panic ran an interview with DeLillo conducted by by Stéphane Bou and Jean-Baptiste Thoret.

Fortunately we now have a translation back to English, thanks to Noel King. The conversation revolves largely around Cosmopolis.

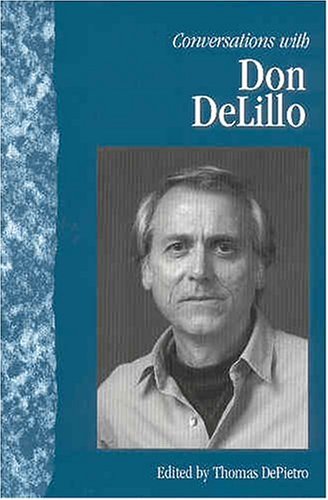

Thomas DePietro has edited a volume of DeLillo Interviews (these are previously published, not new), entitled Conversations with Don DeLillo (University Press of Mississippi, 2005).

Included in the book are the following interviews, in full: LeClair, Harris, Rothstein, Connolly, Arensberg, Goldstein, DeCurtis, Passaro, Begley, Nadotti, Howard, Remnick, Echlin, Firestone, Moss, Feeney, and McAuliffe (most of which are listed on this page)

The Frankfurter Rundschau ran an interview with DeLillo on Nov. 20, 2003, headed with the line "Maybe I see some things more clearly and earlier than others" from the interview. DeLillo discusses 9/11, Cosmopolis, conspiracies and terrorists, and other writers. Julia Apitzsch has provided me with a translation; here is the full text. Here are a few excerpts:

FR: Do you remember the first piece you wrote in your life?

DeL: Yes, actually I remember it fairly well. I was seventeen or eighteen and I was writing a short story that was supposed to be like one of Hemingway's. Hemingway was really the greatest for me at that time. And, to be honest, my fascination with him has never entirely faded.

The Los Angeles Times ran an interview with DeLillo on Apr. 15, 2003, conducted by David L. Ulin and titled "Finding reason in an age of terror". DeLillo discusses Cosmopolis, 9/11, terrorism. Here are a few excerpts:

DeLillo: "Terror is now the world narrative, unquestionably. When those two buildings were struck, and when they collapsed, it was, in effect, an extraordinary blow to consciousness, and it changed everything."

"For the first time in American history we have a much greater sense of our own peril, of our own mortality, a sense that the future is not secure. We've always owned the future, at least in our lifetimes, and now we don't anymore."

The Daily Princetonian ran a short interview with DeLillo on the occasion of his visit to Princeton University as a Belknap Visitor on Oct. 16, 2002 (the story ran on Oct 17). The full story is online. Here are a few excerpts:

"I live in it, and I try to understand it," DeLillo said of American culture. In the 21st Century, DeLillo says being an American has a new meaning. "It means to be worried, perhaps as never before.

"In the years of the Cold War there was danger, there was the danger that an enormous cataclysm might take place, affecting virtually everyone on the planet," DeLillo said. "The danger is different now. The danger is much more specific. The world isn't going to be destroyed, but you don't feel safe anymore in your plane or train or office or auditorium."

DeLillo also remarks that he doesn't "see an end in sight"

with regard to his future writing.

Revue Française d'Etudes Américaines. "An Interview with Don DeLillo" (interview actually conducted March 11, 1999). Pages 102-111, Number 87, January 2001. Focuses on Underworld, with a quick query on 'Valparaiso' at the end.

Q: Couldn't we connect this structural arrangement with the role the ball plays in the narrative?

DD: The ball generates the narrative. Again, this is not something I planned... I did not know that Nick Shay would own the baseball when I began to conceive of him as a character and when I began to write Part 1. It didn't ocur to me for maybe three or four chapters into Part 1. It probably sems obvious to the reader that the main character is the guy who owns the baseball; that's why he is the main character. It did not occur to me, it had to occur to me as a revelation. I suddenly said to myself, "This is the guy who owns the ball! How obvious and how wonderful!". And again, this was another moment, like the backward structure of the book, in which I felt I was at the receiving end of instructions from some empyrean place.

Q: ... in what ways does playwriting add to your experience as a novelist?

DD: The excitement of theatre is palpable but the frustrations, and the complete absence of a definitive evening--the play as text means practically nothing in a way--, there's no particular performance that is definitive in the way a novel is a solid object you hold in your hands and here it is. You can't say that about a play. If the novel gives us a sense of throbbing consciousness, theater is pure soul, beautiful and elusive.

South Atlantic Quarterly. A brief interview with DeLillo focusing on his plays. Published in South Atlantic Quarterly 99.2/3 (Spring/Summer 2000), pp. 609-615. Here's a brief section on DeLillo's perceptions of audience reaction:

DD: And what I sensed most recently with 'Valparaiso' was a thoughtfulness-

JM: On the part of the audience?

DD: Yes, a sense in which they were very receptive, line by line, to what was being said and what was being conveyed to them. And also, and this was perhaps even more curious, a sense that I'd written quite a strange play, which hadn't occurred to me. It hadn't occurred to me through all the days of rehearsal. It did occur to me in the presence of an audience, because that's what they seemed to be feeling. A sense of the play's strangeness.

Boston Globe. "Unmistakably DeLillo - Novelist turns playwright, but menace and meaning remain." Published January 24, 1999.

"Writing as a Deeper Form of Concentration" an interview by Maria Moss conducted on November 14, 1988 in Berlin. Appeared in Sources #6, Spring 1999, pp. 82-97. The entire interview, along with an introduction by Francois Happe is online.

Q: In Underworld you are describing baseball as some kind of American family ritual. And, of course, in The Names, there are the ritual killings by the cult. What is your interest in ritual?

DD: In The Names my interest was the way in which a mind centered on ritual can so easily slip off into violence. I thought that ritual stripped from the world becomes dangerous, becomes violent. It loses its connection. It's almost pure silence devolving into nuclear weaponry, in a curious way, in the way a theory, a formula on a blackboard, like E=mc2, progresses into a bomb explosion on the other side of the world. It's a little like that. These people had removed themselves from the world. And they were acting out of an impetus of pure mind. I felt this could lead to what it did lead to: ritual killings.

WeekendAvisen, Denmark. "The Triumph of Death"

an interview by Bo Green Jensen, November 13, 1998.

(English translation by

Jakob Schelander).

BGJ - You were born in 1936. How did The Cold War effect your daily life, when you were a young man in the Bronx?

DD - I remember when I was 16 and watched a movie, a news cast, which showed the first H-bomb explosion. I recall the speaker, I can still hear his voice, he was in the ship's stern somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, maybe Bikini, as they named the bathing suits after. And there was something terrifying about it, but at the same time it was very entertaining. There was this vision, the iconographical flame, the atomic anger. The mushroom cloud was beautiful and for me it became the determining picture for the culture in the second half of the 20th century. These complex matters are all weaved into our perception of the danger we were exposed to, of the way we escaped extinction. Something we haven't yet made exactly clear to ourselves.

Die Zeit, Hamburg, "Mr. Paranoia" an interview by Jörg Burger, October 8, 1998, ZEIT magazin. (English translation by Tilo Zimmerman).

DeutschlandRadio, "Ein Gespräch mit Don DeLillo" radio interview by Denis Scheck, September 29, 1998.

A radio interview conducted by Michael Silverblatt for the Bookworm show on KCRW. The show is available in Real Audio on the KCRW website. January 15, 1998.

The Irish Times featured a DeLillo interview entitled "And quiet writes the Don" by Fintan O'Toole on January 10, 1998.

The Guardian published on January 10, 1998 "Everything under the bomb" an interview by Richard Williams.

The Telegraph published "They're all out to get him" an interview by Mick Brown on January 10, 1998. Brown met DeLillo in Manhattan and they have a wide-ranging conversation. Here's one bit about a trip driving in India during the Greece period:

We saw amazing things. In that great whirl of humanity there's a curious sort of pattern. You pass a hillside full of saris drying. I have a vivid memory of seeing a woman in a magenta sari and behind her on a stone wall bougainvillaea precisely the same colour as the sari; that kind of thing happened all the time. We passed a village where everybody seemed to be wearing white. For about four days I was in a totally elated state. The same thing happened to me once in Venice, in winter. And it was a kind of privileged state, totally above ordinary life.

Washington Post features an article on DeLillo entitled "Don DeLillo's Hidden Truths" by David Streitfield (Nov. 11, 1997, p. D1).

DeLillo on the novel:

If any art form can accommodate contemporary culture, it's the novel. It's so malleable - it can incorporate essays, poetry, film. Maybe the challenge for the novelist is to stretch his art and his language, to the point where it can finally describe what's happening around him. I still think that's possible.

Hungry Mind Review published The American Strangeness: An Interview with Don DeLillo by Gerald Howard (DeLillo's editor for Libra). Here's a bit of it:

Howard: As you know, the part of the book that really floored me is the psychic history of the Cuban Missile Crisis in the form of a series of monologues delivered over its duration by Lenny Bruce. From my point of view you don't so much imitate or represent Bruce as channel him. It's a beautiful example of hipster hysteria, irony, scorn, and terror, mixed in precise Brucian proportions. Did you ever actually catch his act?

DeLillo: Just once. There was a place not far from where I lived. It was a club in a hotel, called the Den in the Duane, in Murray Hill of all places. I think Lenny Bruce was a very strong influence on the culture and deserves recognition at the level of Ginsberg and Burroughs and Kerouac. Although of course he was different -- he was not a beatnik, he was a hipster. But the things he released into the culture were important.

"Merging Myth and History" by David Ulin, published in Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1997.

Q: What about the notion that this surrogate reality has supplanted true reality, that we're somehow being overwhelmed? This comes up throughout Underworld, and it's also a theme in your other work.DeLillo: It's as though--I think Susan Sontag said this in connection with photography--reality is being consumed. I think of it in terms of the endless repetition of certain videos that keep appearing on TV news. It's almost as though we are becoming consumers of these moments. It might be a homicide, a beating, a car crash. And they run them so repeatedly, you feel they're trying to obliterate memory in a curious way. It's like a product; you see, it's like the mass production of another product, except it happens to be a moment of reality captured on a tape.

This is all we've got left of nature, this improvised moment of violence. It's not choreographed movie violence, it's something startlingly real. It's real, it's live, it's taped. It's so enormously appropriate to this time, when there's a tremendous preoccupation with the image. That's been happening for a long time, but it seems to be deeper now, and woven so thoroughly into our perceptions that maybe it is hard to tell what is real and what is on film.

Witnesses to dramatic moments constantly say, "I thought I was in a movie. It was just like a movie."

"I needed to wait thirty years before writing about it to do it justice. I needed this distance. Also, I needed to write about it in a much larger context. I couldn't write a novel about a background and a place without putting it into a deeper setting. I plunged into the Bronx in my early stories, but the stories weren't very good. I wouldn't even care to look at them now. They were a kind of literary proletarian story. They were about working-class men under duress."and about Geeorge Will's 'bad citizen' quip: "I don't take it seriously, but being called a 'bad citizen' is a compliment to my mind. That's exactly what we ought to do. We ought to be bad citizens. We ought to, in the sense that we're writing against what power represents, and often what government represents, and what the corporation dictates, and what the consumer consciousness has come to mean. In that sense, if we're bad citizens, we're doing our job. Will also said I blamed America for Lee Harvey Oswald. But I don't blame American for Lee Harvey Oswald, I blame America for George Will."

"The Ascendance of Don DeLillo" by Jonathan Bing, published in Publishers Weekly, August 11, 1997, pp. 261-3.

Here's a nice quote:

Let me elaborate just a little if I can. There are writers who refuse to make public appearances. Writers who say 'no.' Writers in opposition, not necessarily in a specific way. But there are those of us who write books that are not easily absorbed by the culture, who refuse to have their photographs taken, who refuse to give interviews. And at some level, this may be largely a matter of personal disinclination. But there may also be an element in which such writers are refusing to become part of the all-incorporating treadmill of consumption and disposal.

And some interesting information on DeLillo's editors:

Since his second novel, DeLillo has been agented by Lois Wallace, who does not sign the author to one house for more than one novel at a time. But his resume of editors reads like a Who's Who of the publishing world: Philip Rich edited his first three novels at Houghton Mifflin. Knopf's Robert Gottlieb -- "with the substantial assistance of Lee Goerner" -- edited Ratner's Star, Players (1977), Running Dog (1978) and The Names (1982).

His next three novels were published by Viking. "In each case at Viking, after I published a novel, the editor left. I got along very well with all of them and I'm still friendly with all of them. But this is something that happens in the business. I didn't consider it an enormous problem." Elizabeth Sifton was the editor of White Noise, Gerald Howard edited Libra and Nan Graham edited Mao II (1992).

An interview was done for the Book of the Month club on July 24, 1997.

Q: How is it that you became a writer?Don DeLillo: It's a bit of a mystery, because I didn't write at all as a child, and I did not do much reading, either. I liked to play. The minute I got out of school I started playing street games, card games, alley games, rooftop games, fire escape games, punch ball, stick ball, handball, stoopball, and a hundred other games. I read comic books and I listened to the radio. No one read to anyone else at home. That's why we had the radio; the radio read to us all.

Found this interview out on the web. Here are a couple excerpts:

On "lonely murderers, terrorists, maniacs":

They have such power, they actually change the way we look at the world. There isn't such a difference between violence and popular culture -- they are blended together, mutual. People are attracted by violence. Last month, Charles Manson was on TV.

The interviewer asked him, "Are you crazy?" and Manson replied, "Of course I'm crazy, I am completely insane. But before, it meant something. Now everyone is crazy." This supported my belief that the world had caught up with the dark vision that I spoke of earlier, a lower form of consciousness. Nowadays there are so many Mansons that you can hardly tell them apart--the serial killers. Now they're a part of life. Mailer's book about Gary Gilmore shows how the media attention around the execution becomes more important than the event itself. Personally, I'm convinced that television and the continual repetition of murder that is shown there has a direct connection with the arrival of the serial killer. Technology and violence are interdependent.

On the idea of a lone person changing the course of history:

The European vision of history has to do with masses and power, the American vision is about how an individual is separate from the masses. In this case history occurs in the form of a person who steps out of history. This can be called postmodernism or postindividualism. Film plays an incredibly important role in the American understanding of history. The Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination has been shown on T.V. only once and that was in the 70s. The murder of Oswald has been shown many times and people are sick to death of it, like a Warhol film. Their deaths followed a social distinction.

I have transcribed the brief radio interview with Ray Suarez from "Book Club of the Air" on NPR, August 4, 1994.

"An Interview with Don DeLillo" published in Salmagundi, Fall 1993. Editor's note: "This interview was conducted by Maria Nadotti and appeared originally in the Italian magazine, Linea d'Ombra. The Salmagundi version of the interview was translated by Peggy Boyers and edited by Don DeLillo."

Q. Do you think you could get used to a computer?

A. No, I need the sound of the keys, the keys of a manual typewriter. The hammers striking the page. I like to see the words, the sentences, as they take shape. It's an aesthetic issue: when I work I have a sculptor's sense of the shape of the words I'm making. I use a machine with larger than average letters: the bigger the better.

"Don DeLillo - The Art of Fiction CXXXV", by Adam Begley, published in the Paris Review, 128. Posted online in Oct. 2010 at: Paris Review interviews.

On the words Toyota Celica:

There's something nearly mystical about certain words and phrases that float through our lives. It's computer mysticism. Words that are computer generated to be used on products that might be sold anywhere from Japan to Denmark--words devised to be pronounceable in a hundred languages. And when you detach one of these words from the product it was designed to serve, the words acquires a chantlike quality.

On literature:

We have a rich literature. But sometimes it's a literature too ready to be neutralized, to be incorporated into the ambient noise. This is why we need the writer in opposition, the novelist who writes against power, who writes against the corporation or the state or the whole apparatus of assimilation. We're all one beat away from becoming elevator music.

"Masses, Power and the Elegance of Sentences" by Brigitte Desalm, published in the Kölner Stadtanzeiger, Oct. 27, 1992 (in Cologne, Germany). Translation by Tilo Zimmermann.

KStA: As a writer, how do you deal with the hegemony of the visual?

D.D.: There are two categories of writers, it could be said: The author who is just a voice, and the one who is also creating a picture. I belong to the latter, because I have an acute visual sense. I am not an opponent of the proliferation of pictures in our culture, I am just trying to understand its impact. I like photography, I like to look at photographs and paintings. However, the difference between the world of pictures and the world of printed matter is extraordinary and hard to define. A picture is like the masses: a multitude of impressions. A book on the other hand, with its linear advance of words and characters seems to be connected to individual identity. I think of a child learning to read, building up an identity, word by word and story by story, the book in its hand. Somehow pictures always lead to people as masses. Books belong to individuals.

Here is the full text of the interview.

"'D' is for Danger - and for writer Don DeLillo" by Margaret Roberts, published in the Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1992.

Another report on DeLillo in Washington to receive the PEN/Faulkner award. Here's DeLillo on Warhol:

What Warhol was doing was sort of ironic, distanced, even comical in a way. And it worked. It's evocative. What he did with Mao in particular was to float this image free of history, so that a man who was steeped in war and revolution seems in the Warhol version to be kind of a saintly figure on a painted surface, like a Byzantine icon. In a way, this was another bit of perverse genius on Warhol's part, because there's no difference in the Warhol pantheon between Mao and Marilyn, or Mao and Elvis.

"Don DeLillo's Gloomy Muse," by David Streitfeld, published in The Washington Post, May 14, 1992.

DeLillo was in Washington D.C. to receive the PEN/Faulkner award. This interview gives a possible illumination of the roots of "Pafko at the Wall":

[DeLillo] mentions a passage in John Cheever's journals. After a ballgame at Shea Stadium, Cheever decided that "the task of an American writer is not to describe the misgivings of a woman taken in adultery as she looks out of a window at the rain but to describe 400 people under the lights reaching for a foul ball ... [or] the faint thunder as 10,000 people, at the bottom of the eighth, head for the exits. The sense of moral judgments embodied in a migratory vastness."

"Terrorism and the Art of Fiction" by William Leith, in The Independent, August 19, 1991, Sunday Review Pages 18-19. DeLillo says: "I don't like the media spotlight. I'd just as soon do no interviews, talk to nobody. And soon I intend to drop out altogether."

"Wired Up and Whacked Out" by Gordon Burn, in the Sunday Times (London), August 25, 1991, magazine section, pp. 36-39. Surprisingly, provides a bit more information for the sketchy DeLillo biography. DeLillo says: "I'm not happy being a public figure."

"I Take the Language Apart" by Nora Kerr, published in New York Times Book Review June 9, 1991 (short telephone interview accompanying a review of Mao II).

DeLillo says:

Not long ago, a novelist could believe he could have an effect on our consciousness of terror. Today, the men who shape and inflence human consciousness are the terrorists.

"Dangerous Don DeLillo" by Vince Passaro, published in New York Times Magazine, May 19, 1991.

Nice quote:

"I used to say to friends, 'I want to change my name to Bill

Gray and disappear.'"

"An Interview with Don DeLillo" by Kevin Connolly, published in The Brick Reader. Interview conducted in 1988 in Toronto.

On the "chief shaman of the paranoid school of American Fiction" tag:

It didn't annoy me. I could take it as an observation about Libra and not disagree strongly. I don't consider myself paranoid at all. I think I see things exactly as they are. William Burroughs has said that the paranoid is the man in possession of the facts. Once you know the facts, people who don't think you're crazy. It's impossible to write about the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath without taking note of twenty-five years of paranoia which has collected around that event.

"The Day John Kennedy Died" by Jonh Wilde, published in Melody Maker, Nov. 19, 1988, pp 52-53.

On writing:

That's how you write novels actually. You suddenly hit upon something and you realize this is the path you were meant to take. You'd be a fool if you didn't follow it. Perhaps it's like solving a difficult question in pure mathematics. There must be a moment when the solution is so simple and evident that you wonder why you hadn't come upon it before. When you do come upon it, you know it in the deepest part of your being. It carries its own logic.

"Matters of Fact and Fiction", by Anthony DeCurtis, published in Rolling Stone, Nov. 17, 1988. A more complete version was later published in Introducing Don DeLillo.

First question:

The Kennedy assassination seems perfectly in line with the concerns of your fiction. Do you feel you could have invented it if it hadn't happened?Reply:

"Maybe it invented me."

Some portion of this interview is available on the Rolling Stone site under this title: Q&A: Don DeLillo.

"Writers Talking", interview with Stephen Fender, BBC Radio 3, November 13, 1988. This is largely a discussion on Libra.

Q: What role is there for accidents and coincidences beyond the plotting? What is the ratio of signal to noise in all this?

A: I think anyone investigating the literature of the assassination finds that he keeps coming across coincidence after coincidence. It begins to seem almost the point of the story after a time. Now this may simply be the case in most dramatic events. Once an event unfolds, it casts a certain light on connections and links between people which we otherwise would not be aware of at all. It may simply be the explosion of a moment which reveals things within the moment which we would not ordinarily have spotted otherwise.

"Don DeLillo, Caught in History's Trap" by Jim Naughton, published in The Washington Post, Aug. 23, 1988. Naughton visits DeLillo at his home in Bronxville, to chat about Libra and other things.

DeLillo began researching Libra by delving into the 26-volume Warren Commission Report that he'd purchased from a used-book dealer. "It gave me a kind of insight into the particulars of the lives of people who testified," he says. "What is it like to work in a train yard in Dallas in 1963? What is it like to be a waitress, a prostitute, a private detective? And all of this comes flowing forth on the page, verbatim, with regional speech patterns, gossip, rumor and in {Lee's mother} Marguerite Oswald's case, all sorts of bizarre global theories intact."Some years ago DeLillo had a brief conversation with Thomas Pynchon, the reclusive novelist to whose work his own is often compared. In their fiction, each is fascinated by the institutionalization of evil, the ascendance of banality and the hovering specter of death. "We were trying to decide whether it was the Penguins or the Platters who recorded 'Earth Angel,' " DeLillo says. "We decided it was the Penguins, but that the Platters may have covered it." He leans back slightly in his chair, hands behind his head and smiles a small, but genuine smile. "The Penguins are pretty obscure," he says. Not to mention pretty correct.

"PW Interviews" by William Goldstein, published in Publishers Weekly, Aug. 19, 1988.

Nice quote:

"Perhaps we've invented conspiracies for our own psychic

well-being, to heal ourselves."

"DeLillo's Novel Look at Oswald: Rescuing History From Confusion" by Elizabeth Mehren, published in Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1988.

The title quote:

There is a set of balances and rhythms to a novel that we can't experience in real life. So I think there is a sense in which fiction can rescue history from confusion.

On Oswald:

I think people also understand that he was almost systematically battered as he tried to make his way in the world. Most of that battering is simply due to the way our society is set up....the classic outsider. But he tried to struggle against the odds, and I think this ultimately produced a greater rage and a greater frustration.

No, I didn't like him, but I understood him. For me that was the beginning of creating a complete character. I felt my way into his mind, page by page. I even developed particular kinds of prose which I took to be a reflection of Oswald's own sensibilities.

"Seven Seconds" by Ann Arensberg, published in Vogue, August 1988.

Q: What role can the writer play in our society at this late date in the century?

A: The writer is the person who stands outside society, independent of affiliation and independent of influence. The writer is the man or woman who automatically takes a stance against his or her government. There are so many temptations for American writers to become part of the system and part of the structure that now, more than ever, we have to resist. American writers ought to stand and live in the margins, and be more dangerous. Writers in repressive societies are considered dangerous. That's why so many of them are in jail.

"Haunted by His Book" by Kim Heron, published in New York Times Book Review, July 24, 1988 (short telephone interview accompanying a review of Libra).

DeLillo says:

I'm sure I'll carry the experience around with me for many years; it's certainly the most haunting book I've ever worked on. Oswald was the focus, but of course the assassination itself sends out tributaries in a number of different directions, from the U-2 incident to the Bay of Pigs.Will we ever know the truth? I don't know. But if someday evidence of a conspiracy does emerge, I expect it will be much more interesting and fantastic than the novel.

"Reanimating Oswald, Ruby et al. in a Novel on the Assassination" by Herbert Mitgang, published in The New York Times, July 19, 1988.

Here's DeLillo on Libra:

Libra is not the modern or technologically brilliant world that characters in my other novels try to confront. This a different kind of novel, a terminus of human feelings. It takes place at the far end of the map.

"I Never Set Out to Write an Apocalyptic Novel" by Caryn James, published in New York Times Book Review, Jan. 13, 1985 (short telephone interview accompanying a review of White Noise).

On White Noise:

I never set out to write an apocalyptic novel. It's about death on the individual level. Only Hitler is large enough and terrible enough to absorb and neutralize Jack Gladney's obsessive fear of dying--a very common fear, but one that's rarely talked about. Jack uses Hitler as a protective device; he wants to grasp anything he can.

"The Heart is a Lonely Craftsman" by Charles Champlin, published in Los Angeles Times "Calendar", July 29, 1984.

There are actually only a few quotes in the article, among

them:

"I'm only nostalgic about two things: our time in Greece,

and the years of Americana, when I was learning to be a

writer."

On writing Americana:

"I stopped worrying about whether Americana would

be published. I knew it had structural problems, and just then

I hadn't a clue how to solve them. But I know I would solve

them. As it turned out, the first publisher I submitted it to

[Houghton Mifflin] took it."

"A Talk with Don DeLillo" by Robert Harris, published in New York Times Book Review, Oct. 10, 1982 (accompanies a review of The Names).

DeLillo on Pynchon:

Somebody quoted Norman Mailer as saying that he wasn't a better writer because his contemporaries weren't better. I don't know whether he really said that or not, but the point I want to make is that no one in Pynchon's generation can make that statement. If we're not as good as we should be it's not because there isn't a standard. And I think Pynchon, more than any other writer, has set the standard. He's raised the stakes.

Published in Anything Can Happen: Interviews with Contemporary American Novelists edited by Tom LeClair and Larry McCaffery.

First question:

Why do reference books give only your date of birth and the publication

dates of your books?

Reply:

"Silence, exile, cunning, and so on." More

on this statement.

DeLillo on his characters:

My attitudes aren't directed toward characters at all. I don't feel sympathetic toward some characters, unsympathetic toward others. I don't love some characters, feel contempt for others. They have attitudes; I don't.

On meaning in writing:

Making things difficult for the reader is less an attack on the reader than it is on the age and its facile knowledge-market. The writer is driven by his conviction that some truths aren't arrived at so easily, that life is still full of mystery, that it might be better for you, Dear Reader, if you went back to the Living section of your newspaper because this is the dying section and you don't really want to be here.