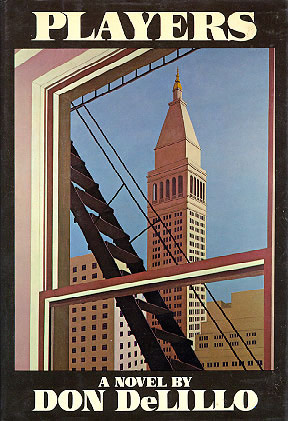

This page lists the known reviews of Don DeLillo's 1977 novel, Players.

I'd be the last to insist that novels include characters who act through intelligible motives. I wouldn't insist they include characters at all. Though most novels have been accounts in intelligibly motivated characters, a good many of them have been nothing of the kind, several of the greatest among them. It does seem fair, however, to ask that the imaginative tranaction that replaces such things on the page have something about it that the reader can find believable and interesting. I am afraid that this cannot be said of most of the writing in Players.

What matters in Don DeLillo's fifth novel about American life is not the plot line, but everything that is happening around its edges: the peripheral movement, a surrealistic swirl of terrorism, anomie and six, into which the central characters and the reader alike are ultimately consumed. The point of view is that of the insider looking out, bu the identity of the insider is full of ambiguity.

The whole point is that people like Pammy and Lyle aren't worth caring about, having played with marriage and money and grief as if all three were abstractions. Even their fantasies are programs on another channel, transpositions. Sex, revolution and death are options, roles, words. Pammy and Lyle would like to be real, and the only way they can think of to be real is to be clandestine. By numbers, by organization, by play, they hope to pull things and themselves into "the illusion of a systematic reality." At the end, the best we can say for either of them is that they are "well-formed, sentient and fair."

With each day's new terrorist event in Entebbe or Wall Street or midtown Manhattan it becomes more natural that terrorists start showing up as prototypical figures in novels; but in novels they have their uses. They replace the car crash as a means of violent and sudden death, replace psychiatrists and holymen as spokesmen of authority. Like the fools in Shakespeare they are satirical; like clowns, with their air of comic befuddlement, they call attention to the significance of things whose significance we had missed. Until their comeback, some of their powers - for instance, the power to effect retributive justice - had been lost to authors. Perhaps they are the only moral agents anyone can believe in now.Still, nobody thanks a moralist, as Don DeLillo must know.

Don DeLillo has, as they used to say of athletes, class. He is original, versatile, and, in his disdain of last years emotional guarantees, fastidious. He brings to human phenomena the dispassionate mathematics and spatial subtleties of particle physics. Into our technology-riddled lives he reads the sinister ambiguities, the floating ugliness of America's recent history.

DeLillo's sensibility thrives on the buzz and hum of New York. There is Wall Street, all granite boxes and chromium towers, with "dizzying billions being propelled through machines, computer-scanned and coded ... money moving ... beginning to elude visualization, to pass from a paper existence to electronic sequences." And the Manhattan streets, crowded with workers and outcasts, buildings and machines - "the woven arrangements of decay and genius that raised to one's sensibility a challenge to extend itself." DeLillo accepts and meets that challenge, but his people are nearly lost amid the powerful rhythms and textures of city life.

What makes this familiar material fascinating is DeLillo's dual perspective: he is a sensor inside the characters and a distant scientist converting signals into informatiion. While Lyle and Pammy proess (and reduce) a world thy're trying to enlarge with adventure, DeLillo decodes both actions. The prose knows how experience turns into abstraction and how people become channels, how plot fades to probabilities and place empties into space, how little becomes less. DeLillo isn't writing scoiology or satire, but the equations for what one character calls "the sensual pleasures of banality."

DeLillo is a spectacular talent, supremely witty and a natural storyteller.... From his first book it was also clear that his control of the language was of a high order. The difference betwen that first book and the latest is what he leaves out. Players is half the size of Americana, but just as dense with implication of the meaning of the lives it presents to us.