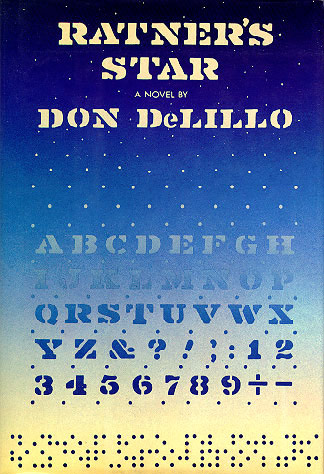

This page lists the known reviews of Don DeLillo's 1976 novel, Ratner's Star.

Don DeLillo's new novel may face the same lack of commercial response as his previous books, End Zone, Americana and Great Jones Street, in spite of its generally positive reviews. For this is, again, an absolutely amazing literary feat, a seriously playful work that transcends categorization. But, unless DeLillo starts attracting a wider audience, his efforts may be relegated solely to the endless analysis of English literature classes.

Midway through his research Billy is told to stop looking for the meaning of the star's message, that is has become irrelevant to the project as a whole. The reader is advised to pay attention to the warning, though, like Billy, he's bound to keep looking of meaning, albeit in a literary sense. The book is, in the end, as elegantly meaningless as a mathematical abstraction, though it is considerably more unnerving and far more entertaining.

Caricatures - such as Micawber, Yossarian, Raskolnikov - fascinate us because their absurdity is made of flesh and blood. The present author's characters, however, are mere lists of curious names. Nobody lives inside them.

How then to capture finally the essence of Mr. DeLIllo's latest and best meditation on the excesses of contemporary thought? I suppose I might apply to the book what one characters says to another about moholes: "In the last analysis, moholes are impossible to talk about. What we're really doing is imposing our conceptual limitations on a subject that defies inclusion within the borders of our present knowledge. We're talking around it. We're making sounds to comfort ourselves. We're trying to peel skin off a rock. But this ... is simply what we do to keep from going mad."

Ratner's Star is not only interesting, but funny (in a nervous kind of way). From it comes an unambiguous signal that DeLillo has arrived, bearing many gifts. He is smart, observant, fluent, a brilliant mimic and an ingenious architect. Too often, however, the razzle-dazzle seems that of a child prodigy, the conspicuous originality somewhat derivative, the dolar unearned, the desperation routine. And the flashbacks to Billy Twillig's family life seem vestigial remains, non-functioning traces of the novel this Menippean satire overgrew. All of DeLillo's books are in an anxious sweat for direct confrontations of the Zeitgeist - which, however, is like a nebula most clearly seen when you look past it or to its side. In Americana, the narrator tells us that "one of my main faults was a tendency to get blinded by the neon of an idea, never reaching truly inside it." and there is some of that in Ratner's Star. But the flashy neon seems pale amid the deep incandescence of this red giant of a book.

Its legions of transitional logicians, mystical mathematicians, and kingpins of alternate physics, and its non-stop display of scientific expertise and pseudo-scientific word games, will probably be well received. Non-whizkids, however, will almost certainly find the constant Mach 2 appearances and disappearances of caricaturish characters confusing; the setting - a futuristic think tank called Field Experiment No. 1 - almost impossible to visualize; and the dialogue, which seems to have been freely translated from Upper Transylvanian, annoying.

To be really disappointing a novel cannot be really bad. What's needed is a developing tension between the author's talent and the reader's hopes on one hand, and the author's performance and reader's frustration on the other. Ratner's Star provides such exquisite tension in large measure. DeLillo knows how to write brilliantly, even movingly, but he doesn't know when he's writing dully, doesn't know when his book has started to die in his typewriter.

DeLillo's aim is to show how the codification of phenomena as practiced by scientists leads to absurdity and madness. It is not his fault that Pynchon is simply better at weaving advanced science and cartoon characters into a convincing whole cloth. Still, Ratner's Star, for all its monotonic monologues, often displays impressive erudition and the same inebriated infatuation with language that worked so well in DeLillo's End Zone, his surrealistic send-up of football and warfare.

Unfortunately, DeLillo's choice of a science-fiction form ("fiction is trying to move outward into space, science, history and technology" he has said) obliges him to reach answers and to impose a dramatic conclusion on his discrete materials. The plot may be intended to appease those hominids still longing for the reassurance of cause and effect, but the many ideas so satisfyingly raised, developed, and clarified in this fine novel deserve a better fate. Still, what a mind-expanding trip to the finish line, and full of wit and slapstick as well.