Some more recent media on Don DeLillo's 1985 novel, White Noise.

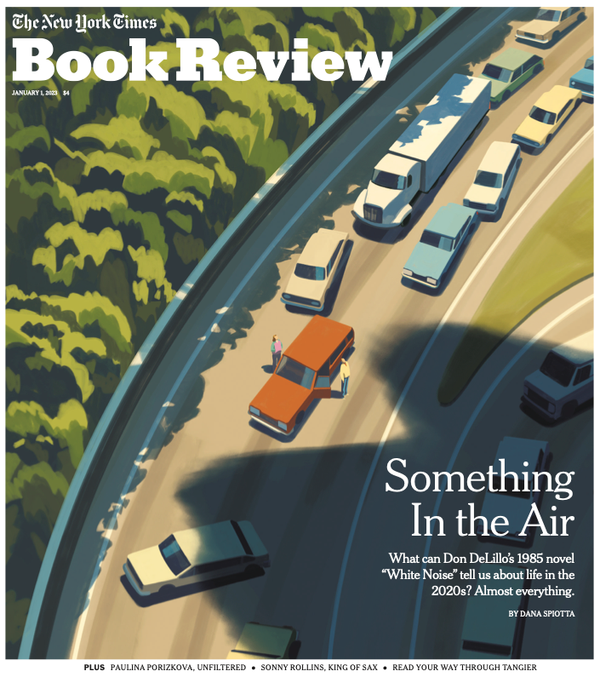

New York Times Book Review: Jan 1, 2023 - Dana Spiotta's appreciation of White Noise, "What a 1985 Novel Can Tell Us About Life in the 2020s: Almost Everything" gets front cover billing.

The book's attention to the "unlocatable roar" of our age also plays out in how the characters react to events in which language both identifies and obscures what is happening. When a plane starts to hurtle to earth, the pilot on the intercom blurts: "We're falling out of the sky! We're going down! We're a silver gleaming death machine!" A plane crashing becomes a machine of death, but DeLillo’s insertion of "silver gleaming" is unexpected, ridiculous, what makes it so funny. We believe and trust technology because humans like gleaming things.

The Millions: Sept 23, 2019 - Writing the Present for the Future: The Mezzanine vs. White Noise by Adam O'Fallon Price.

In White Noise, Don DeLillo — in almost perfect contrast to Baker — looks at his world with the telescopic eye of a priest or pop-cultural anthropologist, beginning with a couple of large-scale hypotheses about modern culture and gathering particulars from there. Anyone familiar with DeLillo could more or less guess what these general hypotheses are, as they run throughout his body of work in various guises: 1) modern consumer culture is similar to primitive culture, and, related, 2) people want to be in cults.

Below, a listing of contemporaneous reviews of White Noise.

Don DeLillo's eighth novel is not extremely long; it just seems that way. Book after book has been greeted by critics as "a novel of ideas." Finally, however, the ideas have overwhelmed the novel. Quite possibily DeLillo - like James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy and Gore Vidal - would be more at home with the personal essay form than the novel. One wonders how many more times, in how many fictional guises, his characters can tell us that life in America today is boring, dehumanized and dangerous.

Once finished, this is a novel one immediately wants to read again.

Yet, as is so often the case in DeLillo's novels there is not consummation or solution. But then nothing else seems appropriate in the cicumstances he so powerfully dramatizes and at the end epitomizes in a scene at a supermarket, the perfect metaphor for the novel's dark vision of contemporary life.

The quickness of DeLillo's writing seems at first rather glib. However, sympathy and seriousness sustain his great supply of funny lines and scenes. White Noise plays off the familiar and the disturbing without ever tipping into the merely grotesque. When DeLillo constantly returns to Jack's quotidian family life, he means his readers to enter a firmly drawn circle that not even a little toxic apocalypse can break.

The toxic cloud, terrifyingly described, is the central symbol of humanity's inability to master its knowledge. But, through tenderness, wit and a powerful irony, DeLillo has made every aspect of White Noise a moving picture of a disquiet we seem to share more and more.

The media are a pervasive presence in White Noise, and may indeed be its true subject (rather than death and the apocalyptic imagination, its ostensible subject). DeLillo shrewdly delineates the way the modern mind adjusts to a daily infusion of bad news, from the death of God to the slow metamorphosis of the nation into one big Love Canal. Comedy this black can always be accused of callousness, and history has underscored this for DeLillo by producing, simultaneously with his book, an "airborne toxic event" in India that will inevitably shape readers' responses to DeLillo's depiction of a similar crisis in an American suburb.

White Noise is a stunning performance from one of our finest and most intelligent novelists. DeLillo's reach is broad and deep, combining acute observation of the textures of American life and analytic rigor. The accumulation of evidence is sometimes indistinguishable from burlesque as, for example, when DeLillo gives all three of Gladney's wives CIA connections. Although DeLillo consciously, and for the most part deftly, mixes modes, occasionally we see the seams between the real and the surreal; at times the observation seems a little too consciously shaped in the service of thematic impulses. But at his best DeLillo masterfully orchestrates the idioms of pop culture, science, computer technology, advertising, politics, semiotics, espionage, and about 30 other specialized vocabularies.

Novelists stay away from prediction. Not to make too much of the "airborne toxic event" in Don DeLillo's new novel, White Noise, and the Bhopal tragedy it anticipates, but it is the index of DeLillo's sensibility, so alert is he to the content, not to mention the speech rhythms, dangers, dreams, fears, etc., of modern life that you imagine him having to spend a certain amount of time in a quiet darkened room. He works with less lead time than other satirists, too - we should have teen-age suicide and the new patriotism very soon - and this must be demanding. But here, as in his other novels, his voice is authoritative, his tone characteristically light. In all his work he seems less angry or disappointed than some critics of society, as if he had expected less in the first place, or perhaps his marvelous power with words is compensation for him.

As far as I'm concerned, in White Noise he means more than he's ever meant before. In the final scene of the novel, Jack's and Babette's youngest child, Wilder, tries to cross a four-lane highway riding his plastic tricycle. ... The boy Wilder is the Gladneys' main comfort in the face of death. To trifle with his life seems positively overheated for a sensibility as icily intelligent as Mr. DeLillo's has always seemed. It is almost as if we were listening to a massive glacier breaking up. The scenery may be arctic, but the noise is not in the least white.

White Noise finds its greatest distinction in its understanding and perception of America's soundtrack.... Fast food and quad cinemas contribute to the melody, as do automated teller machines. Nowhere is Mr. DeLillo's take on the endlessly distorted, religious underside of American consumerism better illustrated than in the passage on supermarkets.

White Noise tunes us in on frequencies we haven't heard in other accounts of how we live now. Occult supermarket tabloids are joined with TV disaster footage as household staples providing nourishment and febrile distraction. Fleeting appearances or phone calls from the Gladney's previous spouses give us the start of surprise we experience when we learn that couples we know have a previous family life we haven't heard about.

Part farce, part satire, part metaphysic, part warning, White Noise is less technically daring, more immediately accessible, than recent DeLillo works such as Ratner's Star or The Names. The story is more an excuse than a compelling fable. There is little in the way of plot, and what is there is deliberately extravagant, even melodramatic. Characters' lives alter, but their personalities remain constant. The tensions develop primarily in individual scenes and moments, the ideas emerge from speculative arguments or meditations and not from action or psychological probing.

White Noise is swoopingly elegant, releasing its opaque insights in a continuous stream of glossily rendered close observation. As with any good novel - as with Dylar - it distances you from death and other personal fears by delivering them through the characters. It is funny. It is irritating. It is baffling. It is clever, modern and celebratory in a downbeat fashion. And like Dylar, it implodes when finished.

DeLillo's gifts are lavish, but his vision is a bit facile. The white noise of the title is electronic static forced into symbolic service as some sort of universal death rattle. Throughout, technology is depicted as the ominous messenger of our common fate; even the price scanners in supermarkets are spooky. Discovering malevolence in things and systems rather than in people is a little callow, especially when DeLillo's solemn moralizing overruns his comedy. Perhaps that is why, after eight books, he still seems like a writer making a debut.

DeLillo's narrative parades its own macabre incons (sic), and tailors them to suit its own eccentric view. White Noise observes a small clique, part of a big country beginning to see sickness in itself. DeLillo's humour is ruthless, isolating television and other vicarious past-times as the causes of the national malady. When Gladney finds himself exposed to a poisonous chemical, he assumes metaphysical proportions, becoming Everyman.

This notion of an analgesic for the Fall of Man is a great and haunting comic idea - although the incidental uses which DeLillo puts it, such as the drug's rather slapstick side-effects, are sometimes less effective than the original notion. The drug's name is Dylar, a word which it is hard not to hear as a contraction of the phrase "die laughing". That usage not only defends this book from charges of bad taste, by reminding us that there is a comedy of death as there is a comedy of love, it also justifies the comic novel as a literary mode.

(DeLillo's) prose is as cooly observant of concrete detail, as obsessed with intellectual balance, as his central character is, whether the matter to hand is a technique for administering drugs or the arrival of students in an endless line of station wagons full of commodities. In the stripped, mocking dialogue of precocious children, we hear a hint of silent and accustomed familial affection and regard: this is an alternatve and unsentimental focus of our response to the novel.

DeLillo becomes increasingly elliptical with every book, as if he's paring his prose to the style of a scientist's notebook. Paradoxically, the distillation is matched by a more subtle and convincing treatment of his characters' inner lives. This broadened emotional vocabulary charges White Noise with a resonance and credibility that makes it difficult to ignore. Critics who have argued his work is too clever and overly intellectual should take notice: DeLillo's dark vision is now hard-earned. It strikes at both head and heart.

This is what makes DeLillo so irritating and frustrating: he's a writer of stupendous talents, yet he wastes those talents on monotonously apocalyptic novels the essential business of which is to retail the shopworn campus ideology of the '60s and '70s. Like his contemporary Robert Stone, whose abilities are comparable, he's more intereted in the message than the medium. He knows how to shape a novel and tell a story, but he's a pamphleteer, not a novelist; he's interested in ideas and institutions (especially malign ones), but not in people. The result is that he writes books that, while their sheer intelligence and style are dazzling, are heartless - and therefore empty - at their core.